Oasis: (noun) a fertile spot in a desert, where water is found; something that provides refuge, relief, or a pleasant contrast.

October 17, 2019

Sebastian Piñera, the current President of Chile, was recently interviewed by the Financial Times. He was eighteen months into his term, which was his second term but not consecutive (his first presidential term was 2010 – 2014). While his predecessor, Michelle Bachelet leaned center-left to left, Piñera was one of the few Chilean Presidents that leaned right. Chile had embarked on a “Chicago School” economic liberalization path that started with the Chicago boys in 1975 under Pinochet’s dictatorship.

The results were nothing short of remarkable. Chile opened its economy by signing Free Trade Agreements with Canada, Mexico and Central America and signed preferential trade agreements with the Andean region countries and Mercosur. In 1982, real GDP shrank by 10.3%, but the country returned to growth in 1984 and in 1989 experienced real GDP growth of 10.6%. Chile has been able to maintain its real GDP growth, with only two years of slightly negative real GDP growth since 1984. By 2006, Chile’s nominal GDP per capita was the highest in Latin America. Chile is the only South American nation that has qualified as an OECD country, becoming a member in 2010.

Piñera has decided to focus his term on boosting economic growth by moving Chile towards becoming a knowledge economy. Doing this will require achieving an improvement in education, increases in science and technology investments, a raising of institutional standards, and a modernization of the state.

“Look at Latin America,” Mr. Piñera said in the interview on October 17, 2019. “Argentina and Paraguay are in recession, Mexico and Brazil in stagnation, Peru and Ecuador in deep political crisis and in this context Chile looks like an oasis because we have stable democracy, the economy is growing, we are creating jobs, we are improving salaries and we are keeping macroeconomic balance.”

One week after Piñera’s interview with the Financial Times, on October 25th 2019, over one million people hit the streets, 25 people were dead to riots, stores were burned down to protest the government, and it was all sparked by a 4% rise in subway rates.

Brazil – The Next Latin American Oasis for Opportunistic Investors?

Purpose of This Newsletter

The model in many ways for Latin American economic progress and advancement has been Chile. Is this still the case? The leader of the main economic reforms driving returns in Brazil currently, Paulo Guedes, was literally in Chile during the country’s period of economic reform. Does he still want to push forward with similar reforms in Brazil? Does he still believe? The goal of this newsletter is to start a dialogue about what his and his economic team’s beliefs and their ability to execute on that basis means in 2020 for global opportunistic investors.

Change is hard. A mentor of mine Mark McGraw says that change only happens when the pain of staying the same is greater than the pain of change. Change is hard stuff. Given what just happened to the “Latin American Oasis” of Chile, the team at InDev Capital thought it was important to reflect, pause, observe, and most importantly – think! Finally, this newsletter hopes to help investors find an oasis, albeit it may be different than what one may think.

The University of Chicago, “The Chicago Boys” of Chile, and One “Chicago Boy” in Brazil

As with many, if not most, countries in Latin America, Chile was a military dictatorship from 1973 to 1990 (Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, El Salvador, Cuba, Venezuela, Colombia, Paraguay, Guatemala, Argentina, Honduras, Brazil, Bolivia, Panama, Peru, Uruguay, and Ecuador have all also had military dictators). After the military coup in 1973 and faced with global headwinds of high inflation, Chile actually went into what could be called a depression in 1975. Chile was a very protectionist country with high tariffs on imports (average of 105%) and high non-tariff barriers. The country’s fiscal crisis resulted in a deficit that reached 55% of expenditure and 20% of GDP, gross savings of 6%, and an investment rate of 7.9%, the worst figures since the 1960s. In 1975, Chile’s GDP decreased by 12.9%. At that time, General Pinochet turned to a group of economists that either had trained at the University of Chicago or were believers in the philosophy of libertarian economic theories championed largely by Milton Friedman at that time.

Chile made some very tough economic decisions, particularly in the context of Latin America, after the 1973 coup that brought Augusto Pinochet into power. While the recent riots in Chile 46 years later need to be respected, one cannot ignore the results of what Chile achieved.

From 1974 until 1985, Chile faced a deep crisis that forced the government’s economic team to enact key economic reforms. Reversing protectionist policies and opening up Chile’s economy was a priority and key area of economic reform. The country opened up trade by introducing a lower flat import tariff rate, which stimulated competition in the domestic economy while simultaneously increasing Chile’s participation in the global economy. Another area of focus was revitalizing and strengthening the country’s private sector, with reforms that included allowing companies to recapitalize via tax incentives, privatizing state-owned companies (and eventually the pension system), encouraging foreign investment in Chile, reforming the banking system, and promoting investment and savings as key policies to revitalize the capital markets.

One example of an industry that was completely revitalized by these economic reforms is copper, today Chile’s number one export. Before private investment in the sector was encouraged, the largest company in Chile was a state-run mining company and the country’s copper reserves were under-exploited (Chile is home to 21% of the world’s economically viable copper reserves). When private companies, as well as foreign companies, were allowed to engage in copper extraction, the sector experienced a boom in exports in the 1990s and 2000. Today, Chile is the world’s top copper producer (approximately 30% global market share), copper is the country’s number one export (accounting for approximately 50% of exports), and copper accounts for 10% of GDP.

Brazil is in the nascent stages of starting a similar effort of economic reform. While not a depression, a very hard recession has driven Brazil to install a similar “Chicago Boy” to help rebuild its economy, Mr. Paulo Guedes. For our purposes, global opportunistic investing, Brazil’s Chicago Boy Paulo Guedes is our president.

Brazil’s shift to a “liberal” economic order (in the classical sense) is not done under a dictatorship but under a young, highly imperfect, and bustling democracy, warts and all. In addition, this democracy includes a President who has a penchant for Twitter, a Congress with no political majority in either house, and a vibrant debate and some legitimate pushback (see Chile) over how far to take these reforms. However, as my mentor Mark states, change only happens when the pain of staying the same is greater than the pain of change. Let’s look at 2020 in Brazil from that lens.

Brazil – It has not been Chile

Anyone that studies Brazil is impressed with its natural resources, the creativity, and talent of its people. Yet, São Paulo, Brazil’s largest city and main economic engine, has the particular distinction of perhaps being the largest important business center that people avoid visiting. (I wish I had a dollar for the number of friends that came to Brazil who I had to meet in Rio as they were not planning to come to São Paulo, not a reflection of São Paulo and perhaps a reflection of my friendships… a lonely writer I am.)

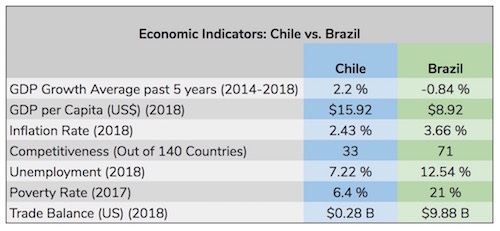

However, candidly, particularly relative to Chile, the country has significantly underperformed its potential, particularly from a GDP growth and GDP per capita perspective, as seen in the table below.

The Pain of Staying the Same – A Forced Change is Still Change

Brazil’s recent downturn, in many ways thankfully, created an urgent situation that has forced change. As stated in these pages before, GDP decreased 8.1% (from April 2014 to Dec 2016), 6 million formal jobs were lost (unemployment increased from 6.8% to 13.2%), interest rates reached 14.25%, inflation reached 10.67% in 2015, and a corruption scandal of epic proportions (approximately R$40 billion, or US$9 billion) occurred. The country was on a path, very fast, in the very wrong direction. The pain of staying the same, not changing, became great enough to cause a radical shift in direction: an impeachment in 2016 followed by the election of a right-wing populist in 2018. A country that had been governed from the center-left or left for 14 years was suddenly governed from the right and, importantly for global opportunistic investors at least, Brazil is now at the start of its own “Chicago Moment.”

Depth of the Big Hole – Markets are Booming – Early in the Cycle

Before Brazil’s crisis, GDP was 2.456 trillion (current US$). In 2016, the depth of the crisis, GDP was 1.796 trillion (current US$). This is important to understand to gauge where we are in Brazil’s recovery. Even though Brazil’s Bovespa stock market increased 31.58% in 2019 and the FII market has grown 35.95%, we are actually still quite early in the recovery of Brazil’s real economy.

Before Brazil’s crisis, GDP was 2.456 trillion (current US$). In 2016, the depth of the crisis, GDP was 1.796 trillion (current US$). This is important to understand to gauge where we are in Brazil’s recovery. Even though Brazil’s Bovespa stock market increased 31.58% in 2019 and the FII market has grown 35.95%, we are actually still quite early in the recovery of Brazil’s real economy.

The country’s GDP growth numbers show this over the past five years. In fact, much of the capital markets’ recovery is based on emotion of the local market more so than hard-nosed objective overseas investors, who usually respond to a stronger economic backdrop.

What we see currently is optimism by the retail investor and the local Brazil-based institutional investor that the country is no longer moving in the wrong direction. But let’s be clear, this is still quite early. There is a lot of capital, in particular a lot of large overseas capital, still on the sidelines.

Paulo Guedes, Brazil’s Finance Minister – Still a Believer

While I have met many people that know the fine gentleman from Rio, admittedly I have not met the man himself yet. I hope to soon. He has quite a background: PhD from the University of Chicago (where he was taught by Milton Friedman), founder of Latin America’s premier investment bank, successful money manager, thought leader, and perhaps most importantly clear economic thinker with many of the right ideas.

Given his economic ideology, I have often wondered how he coped with living in a country that did not follow these ideas and often went in the opposite direction for most of his adult life. As a reader of Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, when Brazil attempted to create a Norway type of safety net with a GDP per capita less than 11% of Norway’s, a population 39 times as large, and significantly lower average education and productivity levels, I assume it must have forced some stiff drinks at some dive bar close to Mr. Guedes’s office over the years.

With Chile now serving as the model of Latin America in crisis, one would think that perhaps our hero, in reality our president, would waver in his belief on his path. The answer is not at all – he is still pushing in the same direction with even more force. From a former business partner of his in Rio, I have heard and I believe this is the moment he has been waiting for his whole professional career. What is more impressive and hugely important is that slowly, but surely, it is working.

Where Are We Now?

Brazil’s economy is slowly starting to gain traction. GDP grew 1.12% in 2019 and is expected to grow 2.4% in 2020. Brazil’s business confidence index increased by 1.25% in 2019, or 1.2 points on the 200-point scale, reaching 97.1, the highest level since 2014. The job market, while still weakened, has started to create jobs with unemployment decreasing from 13.2% at its peak in March 2017 to 11.2% in November 2019. We are still early and this is not bad for investors, in fact it is much better, particularly in a market like Brazil, to be early in the cycle.

Pension Reform

Brazil could be considered infamous for its bloated pension system. An example of the system’s excesses has been in the Brazilian press this month, profiling a 73-year Brazilian woman who worked and currently lives in Paris and receives a monthly pension of almost three times the maximum Social Security payout. What entitles her to this benefit? Her father, now deceased, was a member of Congress and she never married, so as an unmarried daughter of a former Congressman, she has been collecting this pension for 46 years.

Administrations since the 1990s have tried to introduce reforms to the pension system, but reforms have either been unsuccessful or have been passed in watered down versions without significant impacts on the overall system. None of the previous reforms were as far reaching or impactful as the reform package passed in 2019, discussed next.

A pension reform package was approved on October 23rd by the Senate and enacted on November 12th of last year (2019). This long-awaited reform plays an important role in reducing Brazil’s fiscal deficit and keeping inflation and interest rates at healthier lower levels than in recent Brazilian history. The changes to the pension system, which will be phased in over 12 to 14 years, are expected to result in R$800B (US$190B) in savings over the next 10 years. Without this pension reform, the cost of pensions would spiral, resulting in high inflation, and opportunities for overseas risk capital to pursue high risk-adjusted return investments in Brazil would be greatly diminished.

Tax Reform

The federal government is expected to send a tax reform proposal to Congress this year, and it is expected that the reform will be approved in 2020. The proposed reforms aim to (a) simplify the tax system, one of the most complex in the world, thereby improving the business environment and increasing productivity, and (b) stimulate the redistribution of income and decrease the regressiveness of the tax system. The tax reform package is divided into three stages: one, creation of a value added tax (VAT) in the place of the current PIS and COFINS taxes (taxes used to finance federal unemployment benefits and social security); two, changes to the federal income tax for individuals (IRPF) to make it less regressive, as well as a revision of the complicated method for calculating corporate taxes (IRPJ); and three, a reduction in payroll taxes, which currently stand at approximately 43%.

Labor Reform

Brazil passed a labor reform package in 2017, but additional measures, considered in some ways to be a second phase of the 2017 labor reform, were passed in December 2019 via the approval of two Provisional Measures. The job market has been slow to recover from the recent recession and, while unemployment has started to slowly decrease, the job market called for additional reforms to stimulate job creation.

Privatizations

The current Bolsonaro administration intends to privatize dozens of state-owned companies to reduce the size of the state by the end of 2022. The federal government ended 2019 with 204 state-owned companies, as well as direct or indirect participation in 632 companies. While some privatizations did occur in 2019, the government has announced a more aggressive plan for 2020 and intends to bring in R$150B (US$36B) from privatizations, corresponding to approximately 1.7% of GDP.

Global Investors and Brazil in 2020

Over the next several months, we will be in touch with our investment ideas for 2020. In fact, I am in NYC as you read this to discuss one of these opportunistic investment strategies. In 2017, it was time to look at distress as we had hit bottom but the overhang of the downturn had a dramatic effect on real asset owners. We discussed this in great detail in this past newsletter and had some success – please see a case study of the investment we executed with a global opportunistic investor and its returns.

As we think about this time in the cycle, we think the following characteristics are critical.

Clear Spread in Private vs. Public Markets – Expect more details on this topic in the coming weeks, but the capital markets in Brazil are quite liquid and likely to remain so as interest rates are at an all-time low. The search for yield by individual and Brazilian institutional investors is strong. It is important to realize that Brazil was a nation where government bonds and bank CDs had double digit yields for decades. With core interest rates at 4.5%, the opportunity to develop assets and seek liquidity in the capital markets is quite real and profitable.

Rapid Path to Cash – Due to this liquidity, while recognizing one can never say never, it is difficult to purchase stabilized assets at an opportunistic price. Hence, any developments should have a simple process, an experienced developer, and most importantly a short development cycle to reach stabilization.

Scale – Any emerging market takes significant brain damage. If a potential investment strategy cannot reach US$25M dollars or north in profits with relatively conservative underwriting… well, life is simply just too short.

Experienced Local Sponsor – There is a saying that Brazil is not for amateurs. This is very true. Along with deep experience, ideally through several cycles and in the asset class of choice, at this time in the cycle there is real value in the sponsor having both debt capital markets and equity capital markets experience or access.

Back to that Oasis, Joseph – Where Is It?

While there are several nice places in the world, the nicest place I have visited that I would call an oasis would be St. Moritz, Switzerland. It is a paradise of the rich and famous. I took a train from Zurich and it was just remarkably beautiful. Perhaps the closest we can get to a Latin American Oasis right now would be a cold beer with our friend Paulo Guedes in a nice bar in St. Moritz.

While there are several nice places in the world, the nicest place I have visited that I would call an oasis would be St. Moritz, Switzerland. It is a paradise of the rich and famous. I took a train from Zurich and it was just remarkably beautiful. Perhaps the closest we can get to a Latin American Oasis right now would be a cold beer with our friend Paulo Guedes in a nice bar in St. Moritz.

Please email me at joseph.williams@indevcapital.com if you can help make that happen. I can’t stay long, St. Moritz is an expensive place (last time I went I was single and had low overhead) and I am married with three kids, but I will definitely pick up the first beer.

Happy New Year, Happy New Decade, Happy Investing and here is wishing you a very large pile of cash on your desk this year!